between the borderlands

between the borderlands

The United States’ Empire of Borders

“The US-Mexico border must be understood not only as a racist weapon to exclude migrants and refugees but as foundationally organized through, and hence inseparable from imperialist expansion, Indigenous elimination, and anti-Black enslavement. US–Mexico border rule intersects with global and domestic forms of warfare, positioned as a linchpin in the concurrent processes of expansion, elimination, and enslavement, thus solidifying the white settler power of racial exclusion and migrant expulsion,” (Walia, 2021, p.21)

To understand the dynamics of queer and trans migration, we must begin by interrogating the formation of the United States’ “Empire of Borders” and their role in exporting violence and destabilizing regions in the Americas through militarization and imperialism. Early nation building and bordering practices in the US were founded on settler colonialism, genocide of indigenous communities throughout the Americas, and the enslavement of Black people for labor (Walia, 2021). Land grabbing and westward expansion was marked by bloody wars that displaced millions, massacres that eradicated entire communities, and the criminalization of Indigenous, Black, Asian, and Latinx survival (Walia, 2021). The cessation of indigenous land, through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Gadsden purchase, displaced thousands of indigenous and mestizo people in the southwest and created what Gloria Anzaldua conceptualized as the emergence of a border culture.

“The U.S-Mexican border es una herida abierta (is an open wound) where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third country — a border culture.

Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants,” (Anzaldúa, 1987, p.17).

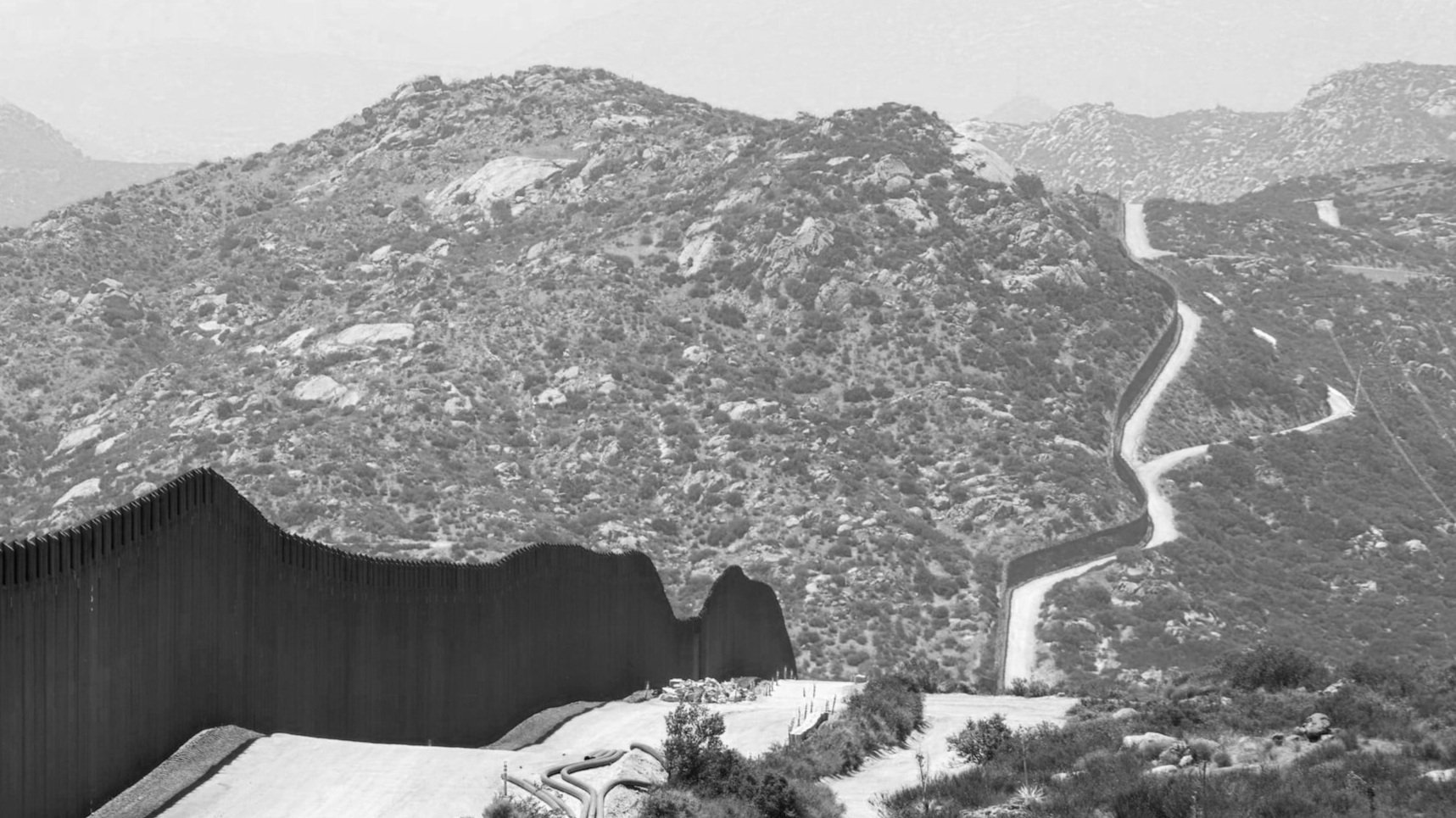

US Border cultures are re-imagined and sustained through different manifestations of militarization that perpetuate othering and criminalize the movement of people. A border patrol with a yearly budget of $25 billion, migrant surveillance technologies from Israeli tech companies, and outsourcing militarization to countries in Latin America upholds the United States commitment to deter the movement of people across the Americas and render neighboring countries carceral nations (White House, 2021). The United States, under the Trump and Biden Administration, has coerced countries like Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala to militarize their border enforcement and deter migrants from moving freely. Just four months after his administration began, the Biden administration announced in a press briefing that Mexico agreed to keep 10,000 troops along their Southern border with Guatemala, Guatemala agreed to station 1,500 police and military personnel along their Southern border with Honduras and operate 12 checkpoints along migrant routes throughout the country, and Honduras agreed to station 7,000 police and military personnel to “disperse a large contingent of migrants,” (White House, 2021). That same month, in a conversation between US Vice President Kamala Harris and Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei, the US agreed to use officials from the Department of Homeland Security to train members of a Guatemalan task force responsible for securing the country’s borders (Perez & Salomon, 2021) The US renders these countries border agents, equipped and trained to protect US interests at the expense of migrants lives and safety (Miller, 2019). In these militarized border zones practices of arrest without charg, extortion, , expulsion, indefinite detention, torture, and killings have become the unexceptional norm, (Walia, 2021). US deterrence policies along the Mexico–US Border, like Operation Gatekeeper, funneled migrants into dangerous and deadly routes in the Sonoran Desert, claiming more than 4,000 thousands lives in the past two decades (Humane Borders, 2021). The externalization of the US border defense, thousands of miles south of the Mexico–US Border, is meant to deter migration from a region in Central America known as the Northern Triangle, comprised of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, but instead, migrants are forced to turn to increasingly expensive, exploitative, and deadly options to and across borders on their journey to the US (Lapp, 2021). Deterrence policies exacerbate the potential for sexual and gender-based violence, with indigenous women, young girls, trans women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community the most at risk of violence from state and non-state actors along informal and formal migrant routes (Duvisac, 2022). The US is exporting and institutionalizing the same type of violence that characterizes the Mexico–US Border throughout the Americas. It will be years before we are able to illustrate the full consequences of the US militarization interventions along the borders, but if it is a reflection of Mexico–US Border governance, it will be marked by state-sponsored violence and migrant deaths.

US Dirty Wars and the Migration Crisis

Historically, US foreign policy, military interventions, and immigration policies, have been an “irresponsible and destabilizing” force in the Americas, “rendering people’s livelihood in Central American countries nearly impossible,” (Villeda, 2021). The migration of Central Americans is painted by the US liberal media and the Biden Administration as “not our problem” but the US is responsible for the destabilization and displacement created by US dirty wars backing indigenous genocide and counterinsurgency terror of the war on drugs (Walia, 2021). The majority of migrants seeking asylum in the US are coming from the Northern Triangle region and have been displaced due to violence, economic and political corruption, and climate change related events.

The United States planted the seeds for the violent ecosystem in Central America to thrive. Transnational gangs such as Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and the Eighteenth Street Gang were organized in Los Angeles by disenfranchised immigrants who fled the civil wars in Central America. (Insert info about civil wars or US intervention in Latin America) The Clinton Administration deported immigrants, including legal residents, who had been convicted of crimes and were involved in the gangs (Montoya, 2022). More than 20,000 people were deported to the Northern Triangle region between 2000 and 2004, fueling the MS-13 and 18th Street presence in the region (Wolfe, 2020).

LGBTQ+ Context in the Northern Triangle and Mexico

LGBTQ+ people from the Northern Triangle are vulnerable to multiple manifestations of violence perpetrated by family members who reject/disown them, gangs that assert dominance over communities, and national and local law enforcement abuse their power (Montoya, 2022). 88 percent of LGBTQ+ migrants from the Northern Triangle reported having been survivors of sexual and gender-based violence in their countries of origin (Amnesty, 2021). 243 LGBTQ+ people were victims of homicide in the Northern Triangle from 2014 to 2019, and unfortunately these numbers reflect a sad reality where intimidation, forced disappearances, and shame leads to a lack of reporting and investigation over anti-LGBTQ+ violence (AICHR, 2015). LGBTQ+ violence often goes unreported in this region as pressure from gangs and their collusion with law enforcement, that also historically discriminates against LGBTQ+ people, forces LGBTQ+ people into a submissive and subordinate silence (Montoya 2022). For LGBTQ+ migrants who are seeking asylum, this corruption complicates their ability to acquire formal government documents that detail the violence they have experienced while in their country of origin or throughout their migration journey. Without proof of reporting the violence, asylum cases are much harder to be won, since immigration judges speculate why asylum seekers hadn’t first sought out a government response. One project participant recounted her experience with violence in her country of origin, describing how gangs that were active in her community were attempting to recruit her to sell drugs. After refusing many times, she started experiencing extreme intimidation and threats on her life. She was forced to pack her belongings in only a few hours and leave her home in secret (Personal Interview, 2023). The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights elucidates the extreme cruelty of anti-LGBTQ+ violence in the region, including cases of torture, stoning, decapitation, burning, and impalement (AICHR, 2015). Experiencing violence and the insecurity of being the next victim, ultimately displace LGBTQ+ people from their families and communities to escape the violence in their home country and find safety and community elsewhere.

In the last decade, social violence in Mexico has increased dramatically due to the violence proliferated by organized militarized cartels and immigration agents. Hundreds of thousands of deaths and forced disappearances carried out by state and non-state actors has marked the political and social landscape (Martinez-Guzman & Johnson, 2021). Women, girls, indigenous people, and LGBTQ+ communities, especially transgender individuals, are most at risk of expressive transphobic cruelty. Mexico is considered the second dangerous country in the world to be transgender. Violence against transgender individuals often go unpunished, including rape and murder (Martinez-Guzman & Johnson, 2021). Queer and Trans migrants, moving through Mexico, continue to experience many forms of violence from state and non-state actors. Mexican immigration agents, and people pretending to be them, are known to regularly stop migrants at various checkpoints throughout their journey and extort money from migrants who are already limited financially. If they are not able to pay the extortion, some migrants have reported being taken away by immigration agents to perform sexual acts to be allowed to continue their journey and appease threats of deportation or imprisonment (US:LGBT Asylum, 2022). One project participant, who identifies as a trans woman, explained how they were taken away by what appeared to be an immigration agent and were forcibly held and assaulted in an unknown location until their family in Guatemala was able to transfer money to their captor (Kendra, Personal Interview, 2023). Human traffickers and smugglers also prey on vulnerable migrant communities, promising to cross them into the United States in exchange for large amounts of money and/or sex work or drug trafficking.

Community Organizing, Survival, Resistance

LGBTQ+ migrants while migrating to the United States survive through many means. No story is the same, but one key element to queer and trans migration that I have come to understand through conversations with the project participants and following the developments of LGBTQ+ community organizing in Mexico, is the existence of, and success of, a formal and informal network of community care that some LGBTQ+ migrants form a part of and tap into to seek assistance and advice from LGBTQ+ serving organizations, communicate with fellow LGBTQ+ migrants, and take care of one another and build community. One project participant, Kendra, said that when they crossed the Guatemala–Mexico border, they felt disoriented and alone. They found out that they had to wait and find shelter and work in Tapachula until they received the proper documentation to continue north, past the migrant checkpoints. Another trans migrant, they had met online, invited them to share a room in a house while they were waiting for the same documentation. Although they had only conversed through WhatsApp, and had met briefly in-person, their proximity and shared experience brought them together. Kendra was able to have a safer place to stay for the duration of her time in Tapachula, a city in the Mexican–Guatemalan Borderland. Although it was not perfect, she expressed her gratitude and happiness to have found some camaraderie while migrating.

There are organizations and institutions throughout the Borderlands that are committed to migrant rights, however there are much fewer that center the experiences of queer and trans migrants. For this project, I collaborated with Jardín de las Mariposas (JDLM). JDLM is a migrant shelter for the LGBTQ+ and HIV+ people. They are located in Tijuana, Mexico, just a few miles away from the US–Mexico border. The shelter used to operate as a rehabilitation center for LGBTQ+ people but in 2017, everything changed when groups of LGBTQ+ migrants migrated together in solidarity and in community with one another. Instead of migrating by themselves, their group grew as they traveled north, providing safety and care for one another. To respond to the need for shelters for LGBTQ+ migrants, the local government asked JDLM to open their doors to migrants, and since then their mission has been to shelter queer and trans migrants. At JDLM, LGBTQ+ migrants were provided with a bed, food, access to an immigration lawyer, and various programs centered around community healing, arts making, political education, and community organizing. The director of the shelter, Yolanda Gomez, expressed how important it is for LGBTQ+ migrants to learn their rights, stand up for themselves, and build community with one another. She expressed how many people think their lives will instantly become better once crossing the border, but she stressed how critical building community and organizing around their collective identities and rights as the most essential tool for their survival and liberation (Personal Interview, Yolanda, January 2023). Some of the people that I had the chance to interview while I was at the Jardín, expressed their gratitude for the shelter, the services, and the “madrina”(godmother) which they called Yolanda. Yaritza, a project participant, described how being at the shelter was healing and motivating for her. She had never been around so many other trans women before and felt that she created true friendships and a sisterhood. She explained how in the past due to her violent and transphobic, environment, she had to take long pauses in her transition or in some cases detransition to feel more safe. “Here I am comfortable, I can wear my dresses, paint myself with makeup, and be the trans girl that I am,” she said in Spanish. “I have the acceptance from the other trans girls and feel like we are a community while we are here together and will continue to be one when we cross to the other side.” The shelter as a transitional space has the power to be formative and collective. It was through the community building and the network that was maintained amongst queer and trans migrants who stayed at La 72, a migrants shelter in Tenosique, Mexico, that inspired the 2017 Gay and Trans Caravan. By organizing in numbers, the Gay andd Trans Caravan arrived to the Mexico-US Border, demanding their rights. Their actions brought international attention as it was one of the first examples of queer and trans migrant community organizing of its kind.

In her research in collaboration with LGBTQ+ migrants, Sandibel Borges explores how LGBTQ+ migrants use “homing” as resistance. She claims that acts of homing like creating spaces that make you nostalgic of home, or conceptualizing new ways to view home, and cultivating a chosen family, is how some migrants can experience safety in care throughout their journey.

“When LGBTQ Latinx migrants exercise their power to engage in homing in the face of intersecting forms of violence, their acts are actively political. Such are acts that challenge sociopolitical borders, which are meant to keep migrants separated from their families, communities, and places of belonging. These borders reproduce rigid and binary categories of gender and sexuality. They represent forcible removal from a home and/or a return to a “home” that might not always feel like one. And they are reproduced by and reproduce the rhetoric of us versus them, both in the United States and Mexico, where migrants with little or no structural power are constantly constructed as outsiders… Engaging in creating, recreating, and maintaining multiple and multidimensional homes is representative of their survival, their resistance, and their power.”(Borges, 2018.)

LGBTQ+ migrant shelters have the opportunity to serve as transitional space for migrants to initiate homing. For many, it is their first time co-living or connecting with other LGBTQ+ migrants. This shared experience allows them to communicate with each other with a sincere depth of understanding and solidarity. While I was at the Jardín, I observed some homing and community building practices, such as a group of trans women doing their hair and make up together, sharing stories, and sharing laughs. These moments of queer and trans joy can be seen produced even through the anxiety and uncertainty that many people felt before finding out the date that they will be able to cross the border. Moments like these exemplify the opportunity for greater connectedness and solidarity. Where needs like shelter, food, and security are met, queer and trans people can collectively harness their strength into a powerful display of joy and resistence.

Conclusion

Queer and trans migrants, who are forcibly displaced from their home due to different forms of violence, endure the rapidly shifting and militarized borderlands of the Americas. Mexico and countries in the Northern Triangle have been rendered immigration and carceral agents of the US’s Empire of Borders. By not addressing the issues that impulse LGBTQ+ migrant journeys, and restricting their ability to migrate to the US, countries like Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, under the support and direction of US foreign policies, are planting the seeds to the multiplicities of violence queer and trans migrants experience throughout their migration journey. To survive the instability of the Borderlands, queer and trans migrants tap into and form part of several networks where they are able to seek out resources and advice, build community with fellow migrants, and organize for their collective rights and liberation. Governments are not responding to the type of needs that queer and trans migrants are demanding. Humanity, compassion, empathy, and care are absent from immigration policies and borderlands governance.

To all the LGBTQ+ people and allies reading this: We must show up for our community. We must protect those that are in need of our protection. We must organize with migrant LGBTQ+ communities and through our collective action demand for justice and care. For many queer and trans people, these are scary times that we are living in. Over 400 bills throughout the country, are targeting our rights to exist, to seek out gender-affirming care, to read books centering queer and trans experiences, to learn our history in schools, and even to perform drag. I know that a lot of us are tired of fighting an uphill battle; I know I am. But we must practice hope and expand our movement towards an intersectional liberation that includes asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, incarcerated people, and centers the lived experiences of Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latinx people.